“Value Investing” is basically the formal term for “Investing without Being a Reckless Dumbass.” The school of value investing has developed several core tenets throughout the years, but the first two are the only ones that non-practitioners tend to remember:

- Rule No. 1: Don’t lose money.

- Rule No. 2: Don’t forget Rule No. 1.

Those rules might seem stupidly simple. And they are — but’s also why they work.

This is the 11th installment of The Labyrinthian, a series dedicated to exploring random fields of knowledge in order to give you unordinary theoretical, philosophical, strategic, and/or often rambling guidance on daily fantasy sports. Consult the introductory piece to the series for further explanation on what you are reading.

Value Investing: Take Two

Maybe value investing is slightly different than non-reckless dumbass investing. More accurately, it’s the art of being cheap in order to make a lot of money. The context in which the phrase is generally used is the world of “paper markets”: stocks, bonds, derivatives, etc. On a fairly consistent basis — at least over the last 100 years or so but almost certainly for longer — the best investors in the world have been value investors.

The godfather of value investing was Benjamin Graham, who was a money manager, financial writer, and groundbreaking professor in New York from the 1920s to the 1960s. He was essentially the Babe Ruth of investing. He was stock market Jesus, and his students truly became his disciples, faithfully living by and teaching others the principles he had instilled in them.

You’ve probably heard of Graham’s most famous student from his days at Columbia Business School: Warren Buffett. And of course there are other value investing disciples in the mythical stock market Hall of Fame: for instance, Peter Lynch, who grew the Magellan Fund at Fidelity Investments from $18 million to $14 billion from 1977 to 1990, and Joel Greenblatt, who started the hedge fund Gotham Capital in 1985 and in his first 12 years at the firm averaged an annualized return of 50 percent.

Even the successful Wall Street money managers who don’t claim to be value investors still employ the principles of the discipline all the time. Truly, almost everyone is a value investor to some degree. Your aunt, who buys items only when they go on sale: value investor. Your grandfather, who held the same core stocks in his musty portfolio for 50 years: probably a value investor. Even the carpetbaggers of the Reconstruction Era, who moved to the South from the North in order to acquire property cheaply: definitely value investors.

Everyone should be a value investor, especially the DFS player.

The Rules of DFS Value Investing

In addition to Rules 1-2, which reportedly were Graham’s and were made famous by Buffett, other (real) value investing rules exist, and they form the core guiding principles of many successful investors’ strategies.

And I suspect that many of the best DFS players in the world also follow these rules in various ways in order to find players who add value to their lineups.

What’s especially important to keep in mind is that there are many successful value investors who are private practitioners, basically the stock market equivalent of a lot of the people who play DFS well but not for a living. In other words, to employ the concepts of value investing, one doesn’t need be a professional investor or DFS player. One just needs to know the rules.

In what follows I’m going to lay out three of the core tenets by which value investors abide. These aren’t the only three rules, but I think that looking at these will get us pretty far.

Also, as we go through the rules I’m going to construct a Trend to exemplify just one way in which some value investing ideas can be applied to DFS.

Rule: Buy at a Discount

This rule is what makes Rule No. 1 possible. If one buys an asset at a discount, then one will be far less likely to lose money than if I one buys that same asset at fair value. This is rule might seem obvious, but in investing (as is the case with DFS) there some people who often “pay up” for an asset because they think that it will so drastically outperform other comparable assets that splurging for the premium will be worth it. And sometimes that’s true — but in general paying up (or even paying fair value) isn’t what you do when your goal in investing in a particular asset is to ensure that you don’t lose money.

Of course, the question is always whether an asset is acquirable at a discount. In finance, there are a variety of ways to answer this question. The most straightforward way is to see if a company’s stock price has dropped even though the company’s productivity hasn’t. In other words, if there is a divergence between price to acquire and productivity, then an asset is likely available at a discount.

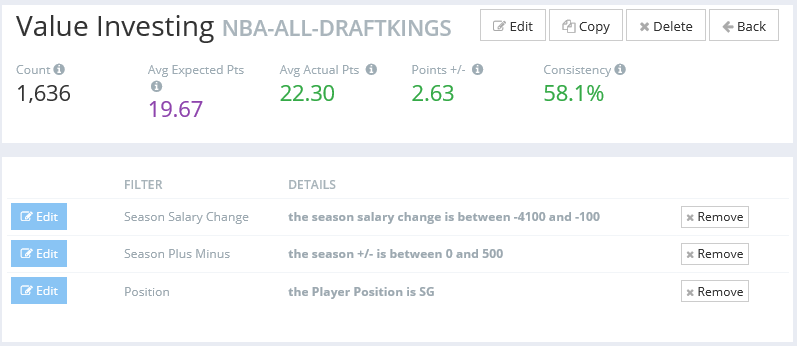

So in the Trends section let’s look for players whose salaries have decreased in the last year but who have been to live up to their salary-adjusted expectations over that timeframe as evidenced by Plus/Minus:

That’s an incredibly simple trend that can add strong value to any lineup immediately. And we can build on it.

Rule: Buy in Depressed or Unpopular Sectors

This rule can be thought of as an extension of the previous one or as a way of guiding you toward assets that are likelier than others to be discounted. The logic goes something like this: In an unpopular or depressed sector, one should have an easier chance of finding companies that are cheap and maybe even cheaper than they should be. By investing in depressed assets, one can minimize downside and also see a large return on investment later, since markets are cyclical and what is unpopular now can become very worthwhile later.

In applying this idea to DFS, I think that it would be best to focus on a position that might be relatively unpopular. Here, I’m thinking about shooting guards. Often people minimize their exposure to shooting guards, not playing them in the guard flex spot or the utility spot if they can help it. In general, people just don’t like shooting guards, because unlike point guards they have fewer opportunities for assists and shots since they don’t play regularly with the ball in their hands and unlike forwards and centers they have fewer opportunities for rebounds and high-percentage shots because they play further away from the basket.

So let’s add shooting guards to the value investing trend:

That works out really well. At a position that sometimes doesn’t offer attractive options, we have been able to identify a trend of significant value.

Rule: Buy When the Experts Do

One of the keys of investing efficiently is allowing other people who are professionals to do for you some of your research on the assets under consideration. For one, they can probably do a better job than you can at analyzing the assets (they might be more competent than you are and they usually have access to more information than you do). Secondly, why do the extra work if experts whom you trust are actually buying the assets themselves?

In general, this “buy when the experts buy” strategy applies to trusted experts who have proven themselves over their careers. Namely, these people are elite money managers, and when they are investing in a company people should pay attention. For instance, if for the last 40 years someone had carried out a “Wager on Warren” strategy and done nothing other than buy and sell the same stocks that Buffett’s company had bought and sold (as evidenced by the company’s quarterly reports), then one would’ve made a lot of money. Mimicry isn’t just a form of flattery. When the right person is mimicked, it can be a form of efficiency.

Justin Phan, who manages the NBA projections for FantasyLabs, is much more knowledgeable at NBA than I am. If the projections like a player, I should probably pay attention to him. Specifically, since a player’s projected production is correlated to the minutes he is projected to play, I should really pay attention to those minutes. If the projections are giving me a “buy signal” by saying that a guy is going to hit a certain threshold of playing time, I should employ the value investor strategy of leveraging the wisdom of someone who is a professional and knows more than I know.

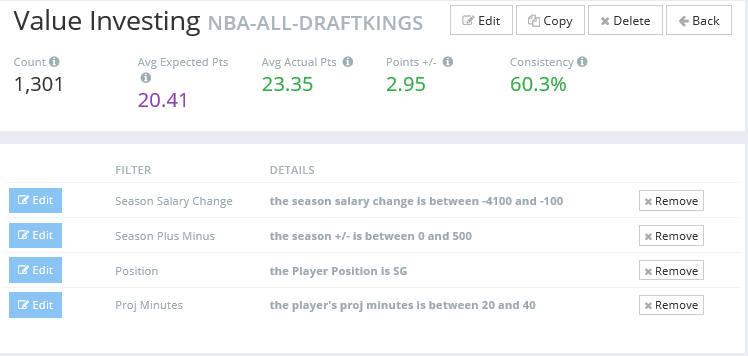

If a player is projected to get fewer than 20 minutes of playing time, he’s almost certainly not someone I want in a lineup. And if he’s projected to get more than 40 points, the odds are decent that his salary hasn’t decreased this year.

So let’s take a look at these buy-low shooting guards who are projected to get 20-40 minutes of playing time:

#ValueInvestorFTW

Buy-Low, Score-Big Shooting Guards

Today’s slate is only three games (I’m writing this on Feb. 18, 2016), but I think it’s a good idea to play small slates as a means of practice. I’ve also written about the contrarian strategy of starting multiple shooting guards in small slates.

This slate, I think that you can combine some of these ideas by starting shooting guards Danny Green and JJ Redick. Both of them are projected to have over 30 minutes of playing time, and both of them fit the profile of the buy-low, score-big shooting guard. In a tournament, they would make an intriguing combination that would increase one’s chances of having unique lineups.

Is it suboptimal to start both Green and Redick this slate? Maybe, but not as suboptimal as it would be to ignore altogether the trend of the buy-low, score-big shooting guards.

———

The Labyrinthian: 2016, 11

If you have suggestions on material I should know about or even write about in a future Labyrinthian, please contact me via email, Matthew@FantasyLabs.com, or Twitter @MattFtheOracle.