Way back when I was in my prime — before all the sex and drugs blogging and data collection — I wrote some books. The Fantasy Sports for Smart People collection is the best-selling fantasy sports and DFS book series of all time. Is that actually true? I don’t know. And if I don’t know, you don’t know, which means I can just say it.

I have maybe a million words of content that I wrote in such a way that it mostly holds the same value now as it did when I first put fingertips to keyboard. No guarantees on the actual quality — just that it’s about the same.

I’ve always been interested in public psychology and how it affects our perception and the ways in which we process information — and, more specifically, how to exploit inefficiencies in the ways people think to make real American doll-hairs. So I’m going to post some excerpts from my books — mostly centered around cognitive biases — that I think should be useful for both fantasy sports players and bettors.

Without further ado, The Jonathan Bales List of Psychological Biases to Avoid for Grown-ups That Can’t Gamble Good and Want to Do Other Things Good Too . . .

Exaggerated Expectations

Based on the estimates, real-world evidence turns out to be less extreme than our expectations

Author and former trader Nassim Nicholas Taleb—someone who has altered my approach to daily fantasy sports more so than probably anyone else, even other DFS players—was a pioneer in the field of tail-risk hedging.

Taleb’s investment strategy, which he describes as antifragile—benefiting from chaos—is marked by long periods of small losses with occasional “jackpots” following rare, seemingly unpredictable events.

In effect, Taleb realized that humans tend to underestimate the odds of low-frequency events occurring (think an extremely powerful earthquake, terrorist attacks pre-9/11 or Tavon Austin catching a pass downfield).

If you think through the math on this, it makes sense. The difference between a 33% probability and 25% probability might seem larger than the gap between 1% and 0.01%, but the latter (1-in-100 vs. 1-in-10,000) is much greater than the former (1-in-3 vs. 1-in-4).

On top of that, because an event with even, say, a 0.1% chance of happening is so rare, it’s difficult to project (and, since there usually isn’t much data in the tails, also often won’t fit within otherwise useful models), and people tend to ignore that which is uncertain.

And we see this effect in a massive way in DFS, specifically in GPP ownership percentages.

In every sport, I’d argue ownership is too high at one end and too low at the other; DFS players as a whole are decent at identifying which players are the high and low-value—the crowd won’t be off in a major way in terms of overall ownership compared against value—but the public tends to be not that close in assessing the relative probability of certain events occurring.

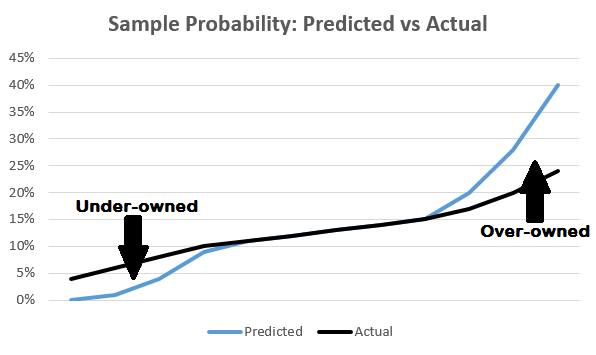

It effectively looks something like this:

In this example, you can see the probability of players reaching a certain point threshold as their value increases. At one end of the spectrum, we have very low-value players who are extremely low-owned in tournaments. At the other end we have high-value players who are extremely high-owned in tournaments. The ‘Predicted’ line is what the market is estimating (with ownership levels) in terms of players’ probability of performing well, while the ‘Actual’ line is reality.

What’s interesting is that even if individuals as a whole are good at estimating the probability of on-field events, the DFS market can still be quite inefficient.

That’s because DFS players are acting in their own self-interest, and thus it’s very difficult for ownership to level out where it “should.” If a player’s “true” ownership should be at 20%, for example, the only way it can stabilize at that point is if DFS players begin predicting not only the probability of certain events taking place, but also how others will predict that probability as well.

How to Overcome/Exploit It

The way to overcome exaggerated expectation is first to understand when past stats are applicable to future predictions.

In football, the answer to that can be ‘not that often’ due to personnel changes, injuries and other moving parts, as well as small sample sizes. If you’re using a second-year player’s weekly consistency from his rookie season to project his volatility in Year 2, for example, there’s a good chance you’re going to get fooled by noise.

Like I said, though, DFS players aren’t necessarily that bad at projecting on-field performance—certainly not as poor as they are at predicting ownership, anyway.

There’s a lot more “meat on the bone” when it comes to projecting what others are going to do in a DFS tournament, so even if it’s theoretically more challenging than predicting on-field results—which is debatable—there could still be a larger usable advantage.

Since the public underestimates the likelihood of low-frequency events occurring, there’s value in rostering at least some low-ownership players because their value, even if reduced, exceeds their ownership. Or, put another way, the market-implied odds of success are lower than reality.

That doesn’t mean that will always be the case; being contrarian isn’t about blindly forgoing value, but rather exploiting public beliefs. Once everyone starts rostering what would otherwise be low-owned players in an attempt to exploit the field, then it’s possible the ownership on high-value players will dip too far such that they’re sharp plays.

Finally, I want to point out that it’s not at all “against the rules” to roster high-ownership players, and I generally prefer a high/low approach to roster construction with both chalk and a few very low-ownership players as opposed to a more moderate strategy.

We know the lowest-owned players are too low and we know the highest-owned players are good values, so I’d rather jump on that certainty than attempt the more challenging task of balancing value with ownership on every player, which often leads to a low-value lineup that’s not even contrarian.

This “extreme” approach to DFS is one I borrowed from another Taleb concept: barbell investing. From “Antifragile:”

What do we mean by barbell? The barbell (a bar with weights on both ends that weight lifters use) is meant to illustrate the idea of a combination of extremes kept separate, with avoidance of the middle. In our context it is not necessarily symmetric: it is just composed of two extremes, with nothing in the center.

I initially used the image of the barbell to describe a dual attitude of playing it safe in some areas and taking a lot of small risks in others, hence achieving antifragility. That is extreme risk aversion on one side and extreme risk loving on the other, rather than just the “medium” or the beastly “moderate” risk attitude that in fact is a sucker game (because medium risks can be subjected to huge measurement errors). But the barbell also results, because of its construction, in the reduction of downside risk—the elimination of the risk of ruin.

Outside of benefiting from chaos, the most useful piece of advice I learned from Taleb is to avoid the middle, where we open ourselves up to more frequent measurement errors.

Pictured: Todd Gurley

Photo Credit: USAToday Sports