I Do Know One Thing

If there is one thing I know, it’s that I know very little. In my brain, I carry bits of random, meaningless information — which help me at trivia night — but I’m not a master of any field, especially one as context-laden as football. (This is probably why I despise the word ‘expert’ as it relates to any fantasy writer.)

So, in an effort to dispel mistruths and discover new ideas, I’m starting a new series on FantasyLabs. Once per week I’ll unload troves of data on a certain topic. Some weeks I’ll dive deep into our free Trends tool. Other weeks, I will focus on certain niche aspects of DFS and fantasy football.

In this piece, we’re going to explore the Average Depth of Target metric (aDOT) and consider why it’s so misunderstood when it comes to wide receivers.

The Myth of High Variance

Our natural inclination is to assume that all receivers with long target depths are high variance fantasy football options and that those with short aDOTs are highly consistent. At the extremes, this is true. A lid-popper like John Brown (2015 aDOT: 15.3 yards) will probably never be a 100-catch receiver while Julian Edelman (2015 aDOT: 7.6) is a reception machine.

But what about the rest of the league? — the wide receivers who don’t have Brown- or Edelman-like extremes? It’s true that aDOT serves as a proxy for variance, but just like yards per reception and other metrics it has clear limitations and is prone to outliers.

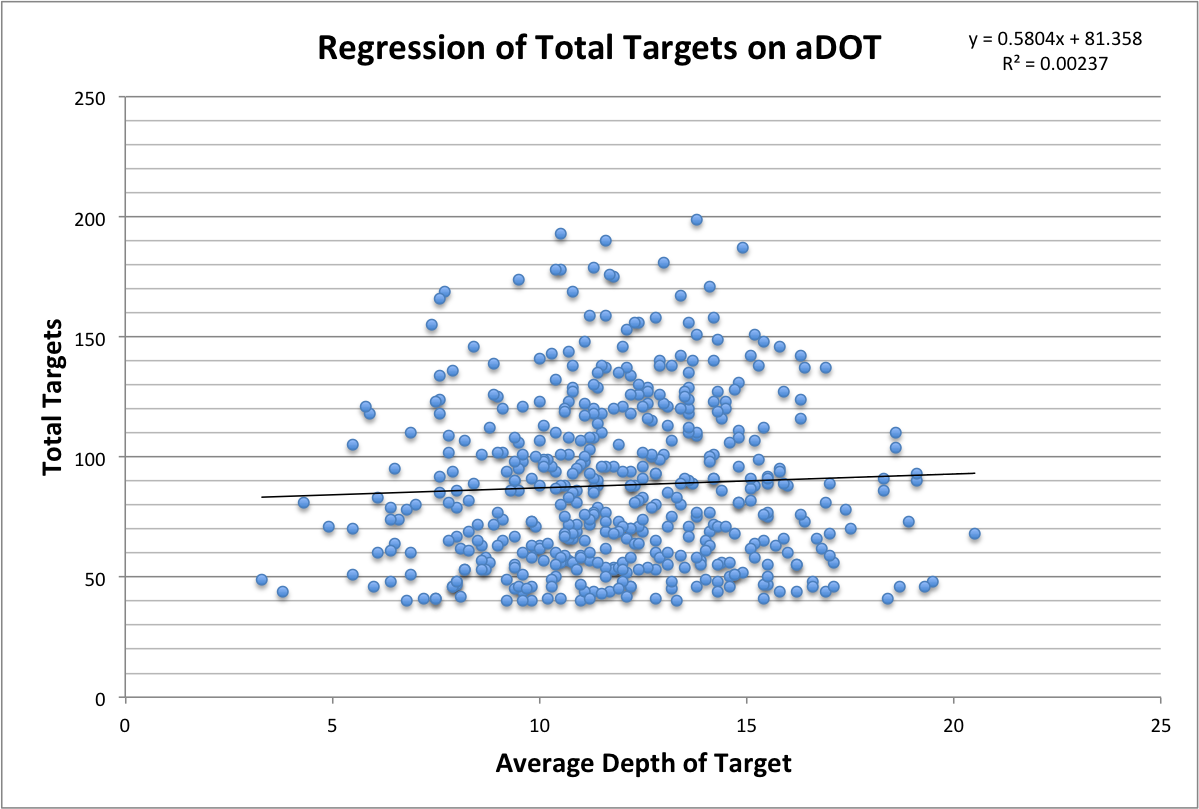

In fact, aDOT does a horrible job of explaining any opportunity-driven statistic, such as targets. To show this, below is a regression analysis of total targets and aDOT. (The data was culled from 2011-2015 from Pro Football Focus.)

Overall, target depth is a putrid way to predict opportunity. A receiver’s aDOT has nothing at all to do with the frequency with which his quarterback targets him.

Target Depth Does Have Some Value

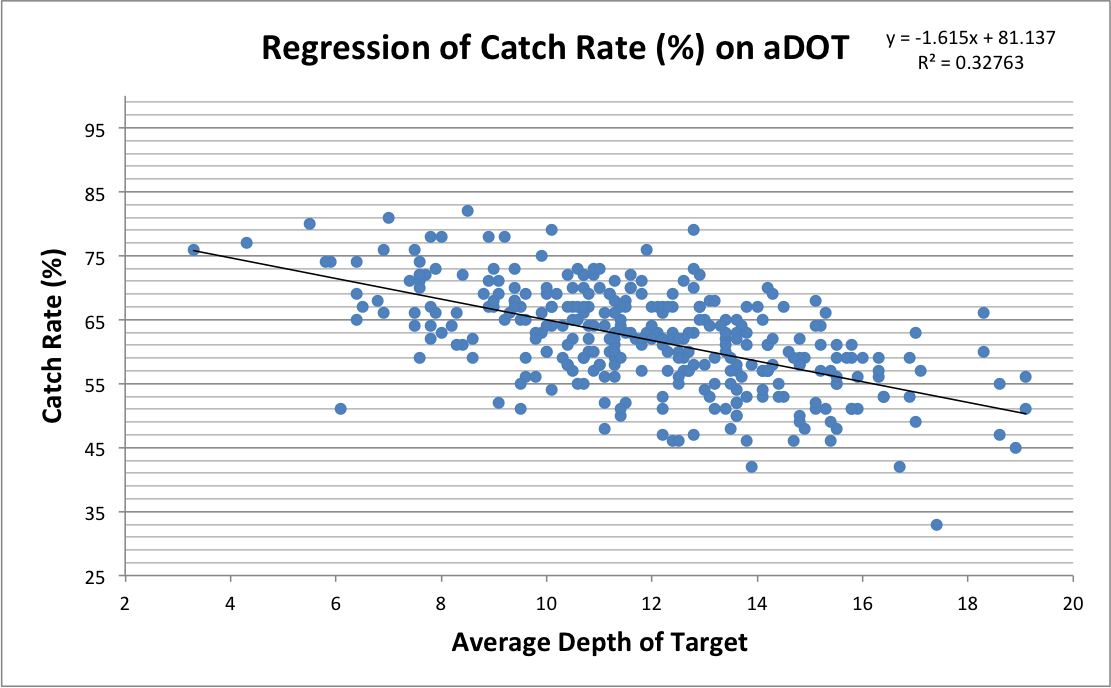

So we know that aDOT isn’t inherently related to volume — but knowing how far downfield a receiver is targeted is useful. In fact, aDOT is predictive of one thing: Catch rate. (Note that the y-axis below begins at a 25 percent catch rate.)

That’s more like it. With an R-squared value of 0.33, target depth is a fine proxy for catch rate.

Intuitively, this idea makes a lot of sense. The further down the field the ball is thrown, the less likely receivers are to catch it.

Why does that matter?

aDOT, Cash Games, and Tournaments

The knowledge that catch rate and target depth are related is powerful information and is directly applicable to DFS.

For cash games, maybe it’s best to roster receivers who not only see a lot of opportunity but also have lower aDOTs. And this might be especially true on sites that award a full point per reception, since catching as many passes as possible in the PPR format is very important.

For guaranteed prize pools, we’re still looking for volume with wide receivers first, but we also want to give ourselves a wider range of outcomes, especially on sites that don’t award a full point per reception, as catching the ball in such a format simply isn’t as crucial. Thus, for GPPs perhaps we should take an extra peak at aDOT, since a lower catch rate is tolerable in the search for Upside.

Upside and other premium metrics are accessible via our free Ratings tool.

Everyone hates Ted Ginn Jr. because he caught only 50 percent of his passes in 2015 and has traditionally struggled with drops in his career. While you should never use a receiver like Ginn in cash games, he made for an excellent occasional tournament play last season, scoring 10 touchdowns in 15 games played. His high aDOT mixed with a respectable 6.4 targets per game made him the boom-or-bust play we all desire on our tournament teams.

The Goal Line

In the end, aDOT can’t predict volume but it does have distinguishable value for cash games and tournaments.