There’s not many things more humbling than when you write articles about how to formulate the perfect GPP lineup and how to maximize upside by stacking and avoiding negative correlations – a big one being opposing running backs – and then a DraftKings user takes down the Milly Maker doing exactly what you’ve been preaching against.

(See a video breakdown of the winning lineup here.)

Of course, I could use this article as a chance to double-down on my thoughts on stacking and correlations and everything else, but I think it’s always good to question yourself and your process. Even if it leads you back to the same thing, that’s fine. But being stubborn in your process and not even being willing to think about alternative strategies is a great way to get left behind.

So, this article is going to do that. Let’s talk about big GPPs and why we may have been thinking about them a little differently than we should have.

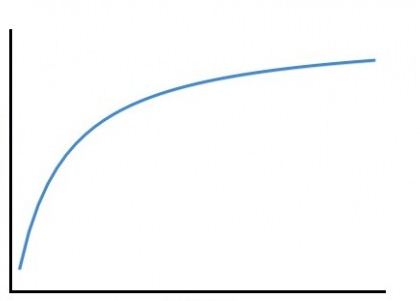

In general, we know the mantra of “Be contrarian, not stupid.” And in general, a lot of smart DFS people would put the opposing RB lineup in the stupid category instead of the contrarian one. And I think it’s because we think of GPPs and the need to be contrarian in this way:

I get a lot of questions from users about how to handle different size contests. In head-to-heads, we know that you should be as safe as possible and maximize your floor. But what about in nine-player contests? Should you be safe still, but add in a little risk? What about 30-player contests? A little less safe, a little more risk?

Obviously, a big part of the answer depends on the payouts – if it’s really top heavy, then you should probably follow the paragraph above and generally get more risky as the player pool increases. But what about the Milly Maker with 500k-plus lineups? At that point, we’re looking at almost complete risk and very little safety, if any, if we follow a linear curve. As such, we use the graph above – continually get more risky, but at a point there will be diminishing returns (think of this as the stupid part) and we naturally level off our riskiness.

I think “Hoothead”’s lineup in Week 3’s Milly Maker might show us that this idea doesn’t level off as quickly as we originally thought. And the reason may be something that I discussed with Fantasy Labs co-founder Jonathan Bales on a podcast a couple weeks ago. We were talking about how a QB and two-WR stack was just 4% owned in tournaments last year. I was telling him that a friend really questioned me on the upside of such a lineup and said, “so you’re banking on a QB going crazy with four touchdowns and two of them a piece to those wide receivers? What are the odds of that happening?” My response was, “Probably pretty small, but isn’t that what you need to win a huge GPP like that anyway?”

And maybe that point is why our thoughts on contrarian-versus-stupid may not be fully formed when it comes to huge GPPs like the Milly Maker. Devonta Freeman and Joseph Randle both ended up being amazing plays, but it’s not like they were really low owned – they were both around 8%. However, I would imagine that the ownership of both together was probably extremely low and there may be a chance that Hoothead had the only one with that combination.

Now, this is not to say that you can’t be stupid in a large tournament – playing a sixth WR that you know isn’t going to get any snaps is still stupid. However, I think you can make the claim that correlations and other factors that maximize your upside are possibly so well-known by the public now that it’s not completely stupid to use a lineup with negative correlations to gain an edge in ownership. It’s the antifragile model – you lower your chances of scoring a lot of points, but you maximize your chances of winning the tournament. And isn’t that the point?